Being Creative is So Embarrassing

art and the digital panopticon In the past couple of weeks I’ve seen a lot of discourse on what people are dubbing the digital panopticon. I began becoming aware of this term through thoughts scattered across tik tok. Eventually I saw it synthesized in Mina Le’s video essay Please Stop Filming Strangers. She, too, likened our current digital culture to Michel Foucault’s use of Jeremy Bentham’s ‘Panopticon’ as a metaphor for behavior under observation. Now, for the purposes of this article, I am not going to go too in depth on the theory of the panopticon as I believe Mina Le and others have outlined it very well and I’ve linked a PDF of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. Rather, I will focus on the idea of the digital panopticon from the perspective of creative process and art.

Briefly, the Panopticon is an architecturally informed system of control designed for prisons. The core idea is that the prison building is round so as to be completely observable from the center by a single prison guard who is not observable by the prisoners. The result, is that though it is impossible for a single guard to observe every prisoner at once, each prisoner will behave as if they are being watched. Foucault used this to describe the relationship between behavior and observation under capitalism. Since, this idea has been likened to cctv and other forms of surveillance. Now it is being used to describe the effect of an almost universal access to high quality video technology and access to social media. In our current landscape, it is as if the panopticon has evolved to where there is no need for a prison guard at all, because the prisoners are surveilling each other and themselves.

Now, I grew up in the cringe compilation era of culture. Like many people in my generation, as a 6th grader I would come home and immediately watch or rewatch Cody Ko videos. Obviously, Cody Ko has earned his cancellation through actions much more heinous than his contribution to cringe culture. But, to me, he was instrumental in establishing the landscape in which we find ourselves in today.

He was one of the first creators I was exposed to that made a living off of filming his visceral second-hand embarrassment from other people’s content. I believe some of his older videos got deleted so it was hard for me to do research, but I recall that most of his reaction videos were harmless, like the Love Island Mobile Game series. Others were even insightful, criticizing hustle culture and toxic masculinity. In compilation reactions there would be mostly morally reprehensible content that, in and of itself, felt as if it justified its own ridicule. But there would be a couple of videos that, in and of themselves, weren’t morally reprehensible but solely “cringe.” Additionally, in videos that focused on one morally reprehensible piece of content, there would be criticism for things that in and of themselves were simply socially unappealing rather than actually problematic. What this does, especially in the mind of a young person, is equate a conformity to a morality. And I think the way the digital panopticon has evolved is largely due to this late 2010’s attitude.

Obviously, there is a developmental necessity that occurs in teens and preteens where we become wary of our identity and how it is perceived by others. But what the digital age has done is turn what should be a brief developmental process into an eternity, fortified by video evidence and enforcing a teenage disinterest under the guise of humility. The result, a generation of people performing humility and monitoring the performance of others(1). If you fail, your punishment is public humiliation. It isn’t humility, it’s self-obsession carefully curated to appear humble.

So how is creativity affected in this landscape? How can an inherently clumsy and vulnerable process survive in such carefully surveilled circumstances? I’m going to share a line that I’m hesitant to, because it feels too earnest. It’s the quote “you, my love, are allowed to suck in every single endeavor,” from Jeff Buckley’s New Year’s Eve prayer and it deeply strikes me. It decorates my desktop background and it lives on the most seen wall of my studio.

“You, my love, are allowed to suck in every single endeavor.”- Jeff Buckley

There are a couple of reasons I find it embarrassing to share. The first being, that when I was 18 someone on hinge told me “you’re not different for listening to Jeff Buckley” when I tried to connect to them on a common interest. My initial feeling wasn’t embarrassment or anger at the passive aggressive comment, it was guilt. Despite how carefully I had curated my personality to slip under the radar of ridicule, I had accidentally fallen into the “pick-me” “I’m-not-like-other-girls” “manic-pixie-dream-girl” trope by talking about Jeff Buckley. Which felt comparable to as if I done something morally wrong. Of course, the aforementioned stereotypes serve a purpose to call out behavior that is immoral and contributes to larger patriarchal issues. But to infer that one behaves immorally based off of their listening history starts to become an issue very quickly.

And I am absolutely guilty of this too. I have made assumptions about people based on their music taste. To a degree it is normal. The issue is when we extrapolate these stereotypes to the realm of morality. We unknowingly paralyze ourselves, in the process, from making or enjoying anything.

The second reason, is the sincerity of the quote. The use of “my love” is flowery, the “allowed to suck” is reminiscent of young adult fiction, and “every single endeavor” is unnecessarily pretentious. But no matter how much I pick it apart as an attempt to circumvent criticism, it’s still a beautiful line to me, perhaps because it was written in an unmonitored moment.

And that’s the issue. Art is conceived in a private place. It is developed and molded somewhere dark and human and then is born unceremoniously into a public perception. Yet, as artists, we are now not only expected but required to form ideas in a glass womb. So at the very moment of creative conception we are aware of the idea being observed. Not only this, but art is fed on sincerity and, as I’ve previously mentioned, there is nothing more unappealing to our perpetually teenage culture than being sincere.

The effect isn’t just dissuading people from making and sharing art, it’s isolating. No one wants to be “the person at the party who picks up the guitar” so we’re less likely to make music together anymore. No one wants to be “the person who thinks they can dance” so we insecurely sway and dodge cameras. No one wants to be “that one annoying kid in class” so no one raises their hand. Our digital panopticon is depriving us of the fundamental meaning of art. Not to create a perfectly authentic yet disinterested piece on our first try, but to connect with one another through one of the best forms of catharsis.

In my personal practice, I’ve been trying to reconcile my desire for a genuine creative process, the need to market my art, and my deeply ingrained fear of being perceived. The only way I’ve been able to so far, is to view the glass womb and the people who can see through it as a part of the art. I’ve been trying to not be at war with social media while at the same time not letting social media dissuade my art making. I’ve been trying to incorporate social media in a way that not only performs well enough but satisfies me. Sometimes I feel like I get there. I strike gold and I manage to appease the algorithm and maintain my sincerity. Sometimes I feel the pressure of the audience looking through the glass womb. I become paralyzed, even when there is no camera like a prisoner of the panopticon.

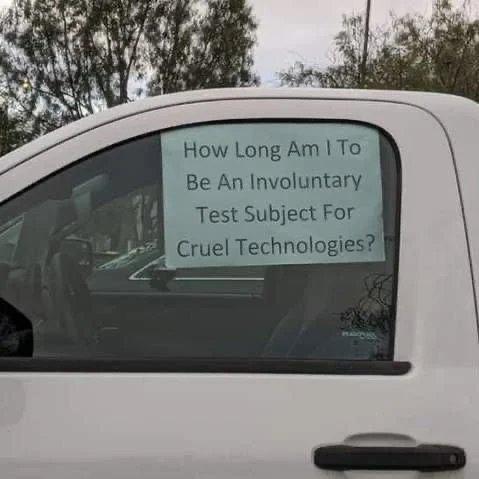

But it’s all so exhausting because the self-surveillance doesn’t end when we stop recording. It doesn’t end when we come home after a day of possibly being filmed by strangers. It is constant self-examination to the most minute detail. It is a constant lens cast inside our own heads to kill ideas in their gestational stage. No wonder we can’t find the will to get out of bed. When our feet land on the ground it won’t be aesthetic, it won’t be consumable, it won’t be perfectly authentic yet disinterested. So what’s the point of even waking when our standard of existence is so unachievable?

What is ironic is that what is actually embarrassing is not the earnestness with which we do things, it’s the intention of them being brilliant. Singing badly, making bad art, saying the wrong thing, these are not moral failures they are the condition of existence. And if we could transform our sarcastic predisposition into loving sense of humor towards ourselves and others so much more art would exist.

Despite everything, I have managed to make some art that does exist! I’ve linked my some products from my shop.

Footnotes:

(1)

I wanted to add what I believe is missing from a lot of this discourse is the inherently ableist element. I’m autistic, and growing up not only did I feel threat of being perceived as socially awkward but I felt as though I had committed a terrible sin if I for a moment faltered in my careful allistic performance. Additionally, I felt terrified of being caught caring on camera. I became deeply tentative in talking about Dan and Phil, Our Flag Means Death, Florence and the Machine, and My Chemical Romance for fear of all the “misplaced” passion tumbling out of me.

For those with higher support needs and intersecting marginalized identities the effect of cringe culture isn’t just isolation, it’s physical danger. When online public humiliation for the crime of being cringe is acceptable it makes the leap to violence against people smaller. I think that, like most issues, the effects of cringe culture uniquely affect already marginalized groups. I think that cringe culture, often unintentionally, reinforces the marginalization of neurodivergent and disabled individuals, particularly putting those with intersecting identities at greater risk of harm.